Price’s definition of the picturesque was in terms of its three objective causes, “roughness . . . sudden variation. . . [and] irregularity, to which he added such other qualities as “sudden, unexpected, and abrupt transitions,” “certain wildness of character,” “variety,” “intricacy,” and “connection”. It enables the viewer to make associations and connections: they are is stimulated rather than calmed or overwhelmed. Price mixed the beautiful and the picturesque so as to limit each other.

The roots of the Australian landscape tradition were in the English picturesque (especially watercolourists) which emphasised the local and familiar and owed much to the topographical movement. In the 19th century the picturesque in Australian colonial Australian painting (eg., Conrad Martens, John Glover) migrated into regional landscape photography. Anne Marie Willis in her Picturing Australia: a History of Photography says that:

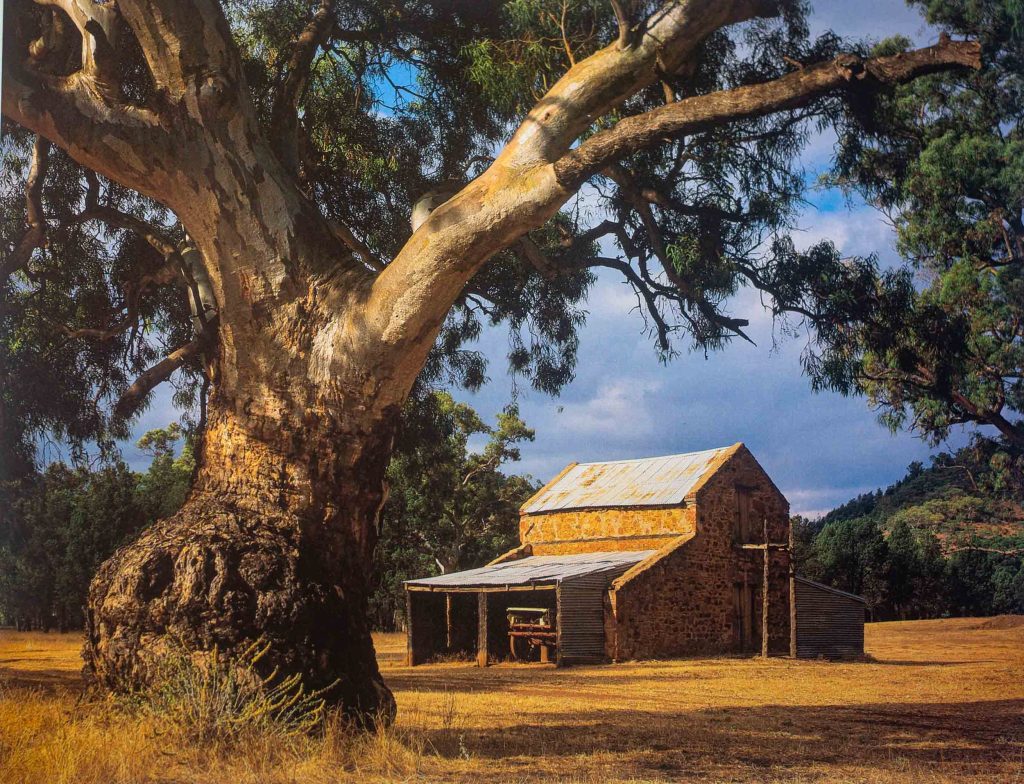

Many landscape photographers working in Australia in the 1860s and 1870s organized their landscape images according to the conventions of the picturesque seeking out elements such as framing trees, foreground logs, winding paths and rivers. These were means by which nature, conceived of as an original wilderness, could be tamed and rendered visibly manageable. Picturesque devices provided a framework for making sense of an alien environment, either by seeking out the familiar or reframing the unfamiliar.”(p. 60)

The picturesque code and conventions in 19th century Australian landscape photography (eg., Jospeh Bischoff, Nicholas Caire, John Watt Beattie and John William Lindt) represented the antipodean landscape not as rugged and inhospitable but picturesque and pleasing to behold — and so ripe for white settlement and colonial exploitation.

This colonial mode of photography intersected with early tourism, Pictorialism (eg., John Kauffmann) and the emergence of nationalism (Australianness). The mode lived on in the twentieth century through its migration into the photography/tourism/exotic location nexus (eg., Steve Parish’s touristic landscapes).

Pippos’ photographic approach to the Flinders Ranges in the above books fits this conception of the picturesque, and his use of this mode of photography can interpreted, less as a visual cliche and more as a reaction to the accurate description and straight photography that was structured in opposition to painting. Art history historically terms the accurate description of the land or country as topographics as opposed to landscape painting, then the picturesque is opposed to utility. It’s approach is always in terms of looking from some point of view, viewing, wandering, or traveling through. The viewer is a tourist or a painter or photographer entering the country or wilderness.

The picturesque as an aesthetic category assumes distance and detachment, and it implies the painter or photographer with a “painter’s eye”. Pippos mode of viewing is one of looking at nature with the careful observation of nature in the careful manner of a painter and a natural scientist. So the picturesque doesn’t just mean “picture-like” ie., modeling our understanding of the aesthetics of nature on the aesthetics of artworks, and experiencing landscapes as “scenery” or a scenic view seen from a distance and a static viewpoint.

Picturesque theory involves, with Ruskin, the actual presence of the past in the present–and not the artificially restored or the imitations of the past–and it also peoples its landscapes with marginal characters.

Traditional landscape painting had been valorized as identical with Australian identity but it was in the process of migrating out of painting into the colour photographs of regional landscapes (eg., the Tasmanian wilderness photography of Peter Dombrovskis) with the photographer as appropriator and reconfigurer of Australian landscape painting. Despite the triumph of photography as a major art form in the 1990s (Bill Henson, Tracey Moffatt and Rosemary Laing) these regional landscapes are seen as culturally conservative, and they were ignored by the modernist art critics and the fashionable magazines of international or globalized art world in Melbourne and Sydney. Pippos’s regional landscape photography is an example of this tradition being ignored by the art world as kitsch’ and ‘chocolate box photography’ .

Pippos’ regional landscape photography celebrates both nature as wilderness and the settler pastoral relationship with the land, which was premised on the dispossession of First Nation’s peoples. It’s particular way of seeing is culturally conservative, as the images of the pastoralist country reinforce a theory and practice of land use, a colonial way of seeing and doing premised on a mastery over nature that is imposed on the land to tame it for reasons of utility. In a post-colonial context the photographer’s gaze and visual order represents the landscape of the historical power of white colonial settlement associated with British imperialism. What is hidden in this representation of the landscape is the dark side of the landscape, namely settlerism concealing the genocide and theft upon which it was founded.

Deploying the English conventions of the picturesque aesthetic makes sense when picturing the natural history of the regional antipodean landscapes, which had been produced in terms of the English picturesque of a pre-industrial Britain. The negative aspect is that the picturesque aesthetic remains within the bounds of a settler colonial culture with its exclusion of indigenous presence. This is the 1990s is a time when the white settler nation, the logic of its narrative history and the inherited history of Australian art had been destablized and was in the process of being pushed aside.

There are multiple and contested histories of the landscape and Pippos’ representation of the Yudnamutana wilderness of the northern Flinders Ranges can be interpreted as a different way of seeing to the colonized regional landscapes; different because it is other to what has been controlled, tamed and exploited. He does not see it as something to be exploited, despoiled and destroyed. It is not a settled, familiar, humanized, arcadian or an idealistic landscape. It is inhospitable country, and alien landscape with minimal human history and deep time. It is an image in opposition to the colonized regional landscapes and part of a tradition of such images that includes an image one of the first artists within Australia to use photography as a reference tool for his painting — W.C. Piguenit’s The Flood of the Darling (1890-1895).

Wilderness photography, which affirms the value of wild nature in opposition to its wanton destruction, is one of the notable omissions from the collections of most Australian art museums and galleries, largely because it was not regarded as art by the gatekeepers in the modernist art institution. In contrast to the US it is deemed to be old fashion and irrelevant, and unable to shed its picturesque conventions for modernism. The art historians (Smith, Hughes, Bonyhardy, Allen, McDonald) argue amongst themselves about what constitutes Australian art and they spill lots of ink over various landscape paintings (eg., Louis Bouvelot,) but don’t even consider landscape photographers. Maybe landscape photography highlights that art history’s traditional concern with an Australian landscape art as a mythic narrative, given the turn in 1990s to globalization, migrant experiences, regionalism and the post colonial turn.

If Tasmania is historically identified with the art and politics of the wilderness photographic tradition (eg., Stephen Spurling 111, Peter Dombrovskis, The Wilderness Gallery on Tasmania’s Cradle Mountain, Chris Bell, Rob Blakers) not South Australia, then Pippos’s wilderness photography in the Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges opens up what has been concealed: the existence of such a regional photography of the South Australian landscape that is constantly being defined and re-defined. Pippos’s photographic project can be linked back to the photography made on both the colony’s 19th century exploratory expeditions and in the early 20th century; and it looks forward to ecology, conservation, environmental sustainability and the shift away from the mastery over nature in the Anthropocene.